How humans interact with Creation is governed by how they view the world. For example, if you view the earth as a square, you would probably be hesitant to travel very far from your home because of the fear that you might fall off the edge. If you believe that the earth is going to be destroyed, you probably will not think that it is very important to take care of.

The actions of farmers regarding Creation and how they practice their farming activities are also governed by worldview. Broadly described, there appears to be two main world views held by farmers. The first one is human-centered or anthropocentric. This view holds that humans are the most important thing and are accountable to no higher authority. This means that humans decide what is right or wrong. Justice in this view could mean ‘just us’ and that the nonhuman Creation has no God-given value, but instead gets value based on what humans decide is important. This view is at odds with Genesis 1 in which God states that His Creation was good even before humans were created. In this worldview, soil is often something to extract yield from and manipulate, instead of a living organism. A counter to this anthropocentric view of Creation is a biocentric worldview, where Creation is exalted over humans. Humans are a pathogen on Creation and threaten the life of the planet.

A theocentric worldview is most compatible with Christianity. This view is that God is the center of all and is in control, humans were created to be faithful stewards of Creation, and all Creation belongs to God (Genesis 2:15; Col. 1:16,20). Farmers are ultimately accountable to God. How a farmer farms based on this worldview requires wisdom, knowledge and deep thought. It means not separating orthodoxy (correct religion) from orthopraxis (correct practice). Ideally, this world view would be held and practiced by all Christian farmers but often farmers unintentionally fall into the anthropocentric worldview or are driven by pure pragmatism.

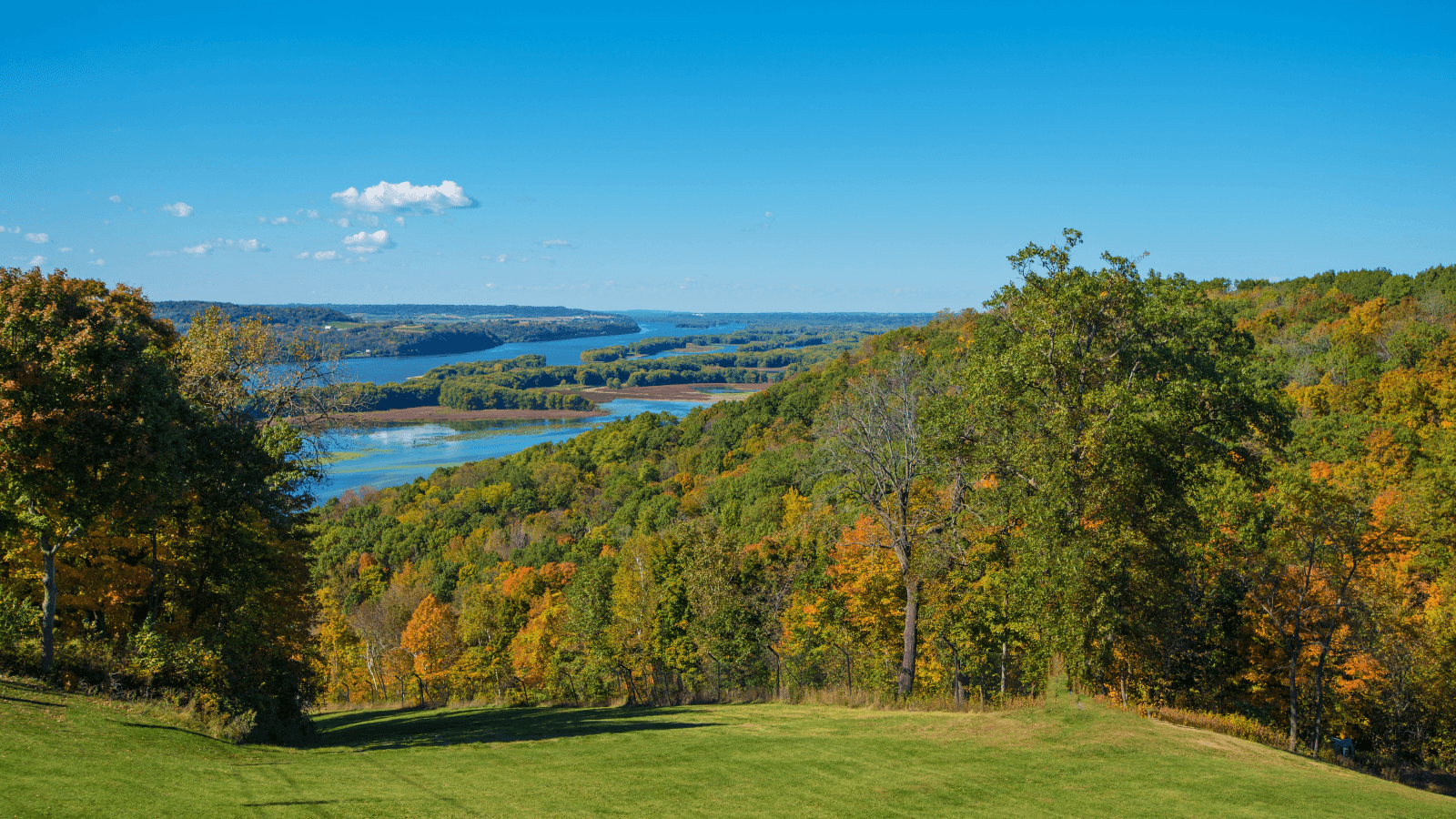

Let’s unpack this a bit. The two great commandments of the Christian faith are to love God with all your heart, soul and mind and to love our neighbors as ourselves (Matthew 22:37-40). For farmers, neighbors are not just people that live near us whom we might know, but they could also be people we impact far away (Luke 10: 25-37). People living downstream in the Mississippi watershed could be considered neighbors because of the impact of farmers’ practices upstream. For example, excess nitrates and phosphates from fertilizer applied to soil moves through the rivers to the Gulf of Mexico causing excessive algal growth. When this excessive growth dies, it uses up oxygen. This causes some ocean life to die and can affect the livelihood of people like shrimp harvesters. Does this square with the second great commandment? What should farmers do when the amount of nitrogen or phosphorus in the soil is much higher than needed by the crop or the amount of manure applied as fertilizer also exceeds the recommendations needed for the crops? Only the farmer will know this-and God! How does a Christian practice a theocentric view of agriculture in these examples?

I offer the following contemporary testimony quote as something to guide Christian farmers in discerning how to farm Coram Deo (before the face of God).

“Grateful for the advances in science and technology, we make careful use of their products, on guard against idolatry and harmful research, and careful to use them in ways that answer God's demand to love our neighbor and to care for the earth and its creatures.” Source: Our world belongs to God. #52